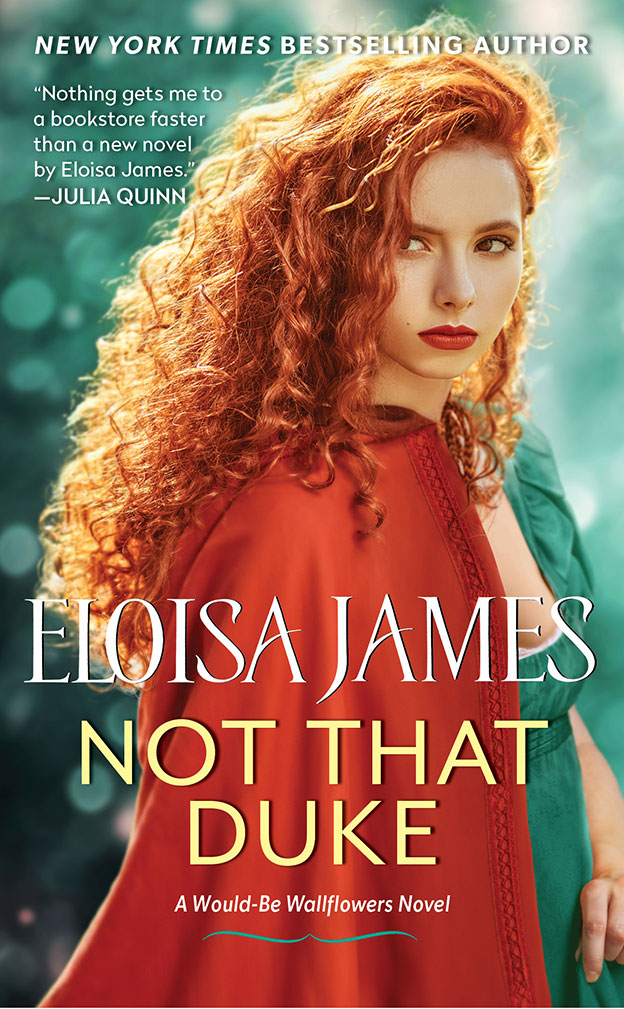

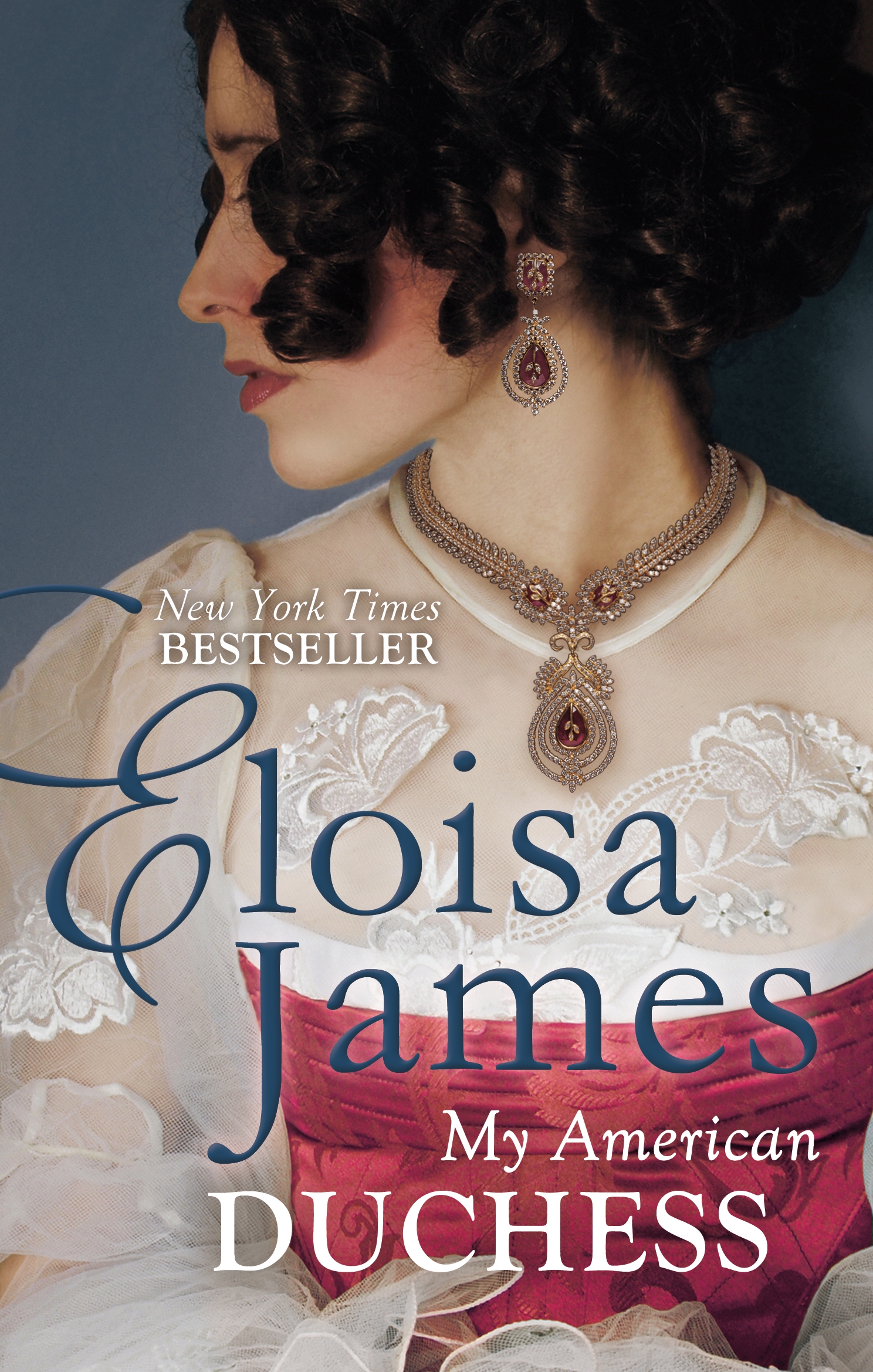

My American Duchess

Part of the Would-Be Wallflowers Series

Would-Be Wallfowers prequel.

The arrogant Duke of Trent intends to marry a well-bred Englishwoman. He wouldn’t even consider Merry Pelford, a madcap heiress who has made herself infamous by jilting two fiancés.

Besides, Merry is in love with his dissolute younger brother—and this time, the former runaway bride has vowed to make it all the way to the altar.

But as Trent and Merry discover, love has a way of complicating their perfect plans…

My American Duchess

Book Extras

Inside My American Duchess

My American Duchess was supposed to be a novella. One of my best friend’s sons, Joe, brought a diamond ring in his pocket all the way from England and asked his beloved Leeanne to marry him in Central Park while staying with us! I decided to write a novella in honor of their romance. But Merry and Trent were so much fun to spend time with…before I knew it, 100 pages had turned to 400!

Prequel to My American Duchess

I have a wonderful present for readers of My American Duchess—a short prequel story featuring Merry’s parents, Clementina and John. Remember how Merry describes her mother as a bit of a rebel, an young English lady who traveled to America and then dared to marry a man without money or name, because she believed in him? Short, sweet, and very romantic!

My American Duchess Deleted Scenes

Here are the deleted scenes from My American Duchess. Try to figure out where each scene fits into the book!

Stepback for My American Duchess

Enjoy the stepback for My American Duchess.

Just How Much Did Merry’s Pineapple Cost?

The pineapple Merry asked for cost anywhere from $5-10,000!

Eloisa and Maya Rodale on American Ladies in London

Maya Rodale and I chat about the new trend of American ladies in Regency London!

My American Duchess

Reviews

"amusing and heart-wrenching"

"A gratifyingly lush, vibrant, and emotional romance."

— Kirkus

"...then wraps the resulting irresistible love story up with an abundance of wit-infused dialogue and a refined brand of sensuality."

— Booklist (starred review)

"Trent and Merry have an explosive chemistry..."

"Filled with winning characters and witty repartee, this Georgian historical is a treat.”

— BookPage

My American Duchess

Enjoy an Excerpt

Jump to Ordering Options ↓

Listen to an Audio Excerpt ↓

April 6, 1803

Lady Portmeadow’s ball in honor of the East End Charity Hospital

15 Golden Square

At 9 pm sharp, Lord Cedric Allardyce gracefully fell to his knees, signaling his intent to request Miss Merry Pelford’s hand in marriage.

Merry stared down at his buttery curls, scarcely believing this was actually happening to her. She had to force back a nervous giggle when Cedric complimented her finger for its slenderness before slipping on a diamond ring.

It felt as if she were on a stage, playing a role meant for a delicate, feminine Englishwoman. That actress hadn’t shown up, and storklike Merry Pelford had taken her place.

But at 9:02, after Cedric’s lyrical proposal drew to a close, she forced back a nervous qualm and agreed to become his bride.

Back in the ballroom, Merry’s guardian, her aunt Bess, didn’t seem to realize that Cedric and Merry were mismatched. “The two of you are exquisitely suited, like night and day,” she said, eyeing Cedric’s yellow hair. “No, midnight and the dawn. That’s not bad; I’ll have to write it down.”

“My aunt is a poet,” Merry told Cedric. He had been courting her for some time, but as yet, he hadn’t spent much time with Mr. and Mrs. Pelford, her only family.

Before Bess could prove her credentials by tossing out a line or two, Uncle Thaddeus—who was bluntly unsympathetic to rhymes of any kind—dragged Cedric off to the card room.

Merry instantly pulled off her glove and discreetly showed her aunt the diamond ring. “Cedric is friends with the Prince of Wales,” she whispered.

Bess raised an eyebrow. “It’s always helpful to be acquainted with those in power, though I can’t say I view the man as a desirable acquaintance on his own merits.”

Merry’s aunt had grown up in that cradle of American high society known as Beacon Hill; her father was a Cabot and her mother a Saltonstall. Her staunch belief that she represented the pinnacle of society remained unshaken in the presence of the most haughty noblemen.

“I am looking forward to meeting His Highness,” Merry said stoutly. She was marrying an Englishman, and that meant she had to adapt English ideas.

“The only prince I’ve met to this date is that Russian who courted your cousin Kate,” Bess said. “There’s nothing worse than a man who bows too much. He popped up and down like a jack-in-the-box; it gave me a headache just to look at him.”

“Prince Evgeny,” Merry said, nodding. “He was always wearing white gloves.”

“White gloves on a man have their time and place. But what with the gloves and the bowing, he was like a rabbit, one of those that flashes its tail before it runs off.”

Aunt Bess certainly had a lively gift for metaphor.

“What a lovely evening,” she continued. “The only thing better would be if your father was with us, but I’m certain that he and your sainted mother are watching over you. Likely he was the one who put the idea for this visit to England in my mind!”

Merry nodded, though she was less certain about her father’s approval. Mr. Pelford had been a patriot to his core, and had been elected to represent Massachusetts in the Constitutional Congress, after all.

He had made his own way in the world, taking the profits from a successful patent for a weaving machine and speculating in real estate, then standing for the House of Representatives. In fact, if he hadn’t succumbed to a heart ailment, Merry thought her father could have ended up President of the United States.

Her aunt’s thoughts must have followed hers, because she added, “Though now I think on it, your father might have disliked the idea. More likely, ’twas your mother. I know she loved the land of her birth.”

Merry brushed a kiss on her aunt’s rosy cheek. “My father wouldn’t have a single complaint. You and Uncle Thaddeus have been the best possible guardians.”

“Such a sweet child you were, from the very day you came to us,” Bess said, her eyes turning misty. “You make up for the lack of my own children tenfold. I can scarcely believe that my niece will be an English lady.”

Merry still couldn’t quite imagine it herself.

“Lord Almighty, this room is overheated!” Her aunt started fanning herself so energetically that the feathers on her headdress billowed like a ship’s sails. “I feel as hot as a black pudding.”

“Why don’t we go onto the balcony?” Merry suggested. Its doors stood open in a fruitless attempt to cool the room.

“If it’s stopped raining,” Bess said dubiously. Once in the cool night air, she quickly recovered. “I find your Cedric dazzling,” she exclaimed, snapping her fan shut. “A title is all very well, my dear, but I think it’s better to judge a husband on his own merits—on the plain naked man, if you take my meaning.”

“Aunt Bess!” Merry tugged her from the open doorway. “You must watch your tongue. English gentlewomen aspire to modesty.”

It hardly need be said that Bess didn’t share their aspirations. “That ballroom is full of women pretending never to have gawked at a man’s wishbone,” she pointed out, “whereas in reality they walk around the room like butchers’ wives at a fish market.”

“English women have very refined manners,” Merry objected.

“So they’d like to think. The proof of the pudding is in the eating, m’dear. Look at the fashions here. I appreciate those silk pantaloons as much as the next woman.”

Merry rolled her eyes. “Aunt Bess!”

“You’re betrothed again, so I can speak my mind,” Bess replied, unperturbed. “Mind you, speaking of pantaloons, your Cedric is certainly a well-timbered fellow.” She gave a throaty chuckle. “That reminds me—I promised to dance this quadrille with your uncle. He’s as clumsy as a June bug, but he does enjoy a nice gallop around the room. Come along, dear.”

“If you don’t mind, Aunt, I’d rather stay here for a few minutes.”

Her aunt gave her a squeeze. “How I love that smile of yours! Your Cedric is a perfect lady’s playfellow. Come your wedding night, the two of you will be as merry as crickets in a fireplace.”

With that, her aunt reentered the ballroom, feathers and fan flapping.

Merry wrapped her shawl around herself to ward off the April air and tipped back her head to look at the sky.

She kept forgetting that no stars shone above London, rain or no. Fog and smoke turned the streets dark by four in the afternoon.

But Cedric loved the city, so they would live here. There was no point in longing for starlight. Or gardens, for that matter.

Merry had a passion for gardens that went beyond her schoolfriends’ delight in arranging bouquets. She liked to “muck about in the dirt,” as her uncle called it, rooting up plants and rearranging them until she had laid out the perfect garden.

Just then a man shot across to the balustrade and muttered a string of oaths that no young lady was meant to overhear.

She drifted a step closer, pleased at the opportunity to augment her vocabulary of forbidden phrases. Alas, the only word she caught was “ballocks,” and she already knew that one. As she watched, his fingers curled around the rail in a controlled but furious gesture.

Most likely, someone had snubbed him, and he’d come out here to regain his composure. English aristocrats, as she’d discovered since her arrival in London, had a penchant and a talent for delivering withering remarks. She’d seen her own darling Cedric issue several snubs himself, though only when mightily provoked.

Why, if she were the type to take offense, she’d be cross at half the guests here tonight, given the way they mocked her Boston accent.

The man glowering down at an innocent whitethorn hedge was probably from one of the lower rungs of the social ladder, someone whom most people in that ballroom would look right through.

In America, he would be free to make his own way, judged on his merits, not his birth. But here? One was born into a social class, and in that class one remained until death.

The man certainly wasn’t wealthy. Cedric’s attire glittered with gold thread and gilt buttons, but this fellow’s coat was as plain and black as a Quaker’s.

Even from where she stood, she could tell that his cravat had no more than a touch of starch and was tied in a simple knot. In fact, he might be without the services of a valet, as his hair was cut short and wasn’t in the least modish.

Perhaps he was American. It would explain his unfashionable hair and coat. With a surge of patriotic fellow-feeling, she moved over to him and lightly touched his sleeve.

When he turned to face her, she knew instantly that she’d been wrong not only about his nationality, but about his rank. The hard line of his jaw and the arrogance of his manner marked him, without question, as a member of the British peerage. Even his hair, the color of tarnished guineas, looked aristocratic.

“I beg your pardon?” His voice was deep—and she thought she heard disdain. He glanced down at her hand, still resting on his sleeve, and she snatched it away.

Oh dear.

English ladies never spoke to strangers, so he probably expected her to cower like a chambermaid. In that case, she would disappoint him. No American flinched before an Englishman, noble or otherwise.

Head high, she met his eyes straight on, and sure enough, a distinct flash of surprise crossed his face. “Please forgive me for disturbing you, sir,” she said, curtsying. “I mistook you for one of my countrymen.”

She could scarcely believe she’d felt pity for the man, because now she had the impression that she was sharing a small space with a large predator. She fell back a step with the aim of returning to the ballroom, but he moved forward and blocked her flight.

“There are a great many Americans in London this season, are there not?” he asked.

Goodness sakes, the man was ferocious looking. It was difficult to imagine who would have had the nerve to affront him; in comparison, her combative former fiancé Bertie was as placid as a cow.

He had made her so rattled that she spoke before she thought. “According to The Times, there are at least three times as many Americans in London as there were a decade ago.”

Merry’s governess, Miss Fairfax, always said that no man wished to be thought ignorant, but Merry was certain that this man wouldn’t give a damn—because he was absolutely confident about what he did know.

Sure enough, he merely cocked an eyebrow and asked, “Did The Times offer an explanation for the swell in your numbers?”

“It did not. But did you know that Americans often study in your Inns of Court? Five men who signed our Declaration of Independence were educated at the Middle Temple.”

She nearly clapped a hand over her mouth. She had gone from inappropriate to objectionable; American independence was hardly a subject about which English aristocrats were enthusiastic.

She dropped a hasty curtsy. “If you’ll excuse me, sir, I shall go fetch my next dance partner.”

Laughter gleamed in his dark eyes. “If I might offer you some advice, no English gentleman wishes to be ‘fetched.’”

His evident amusement eased her nervousness. “My experience of London is not great, yet I have already discovered that there are any number of English gentlemen eager to be ‘fetched,’” she said, giving him a wide smile before she remembered that young ladies weren’t supposed to do more than demurely curl their lips.

“I surmise that you are referring to gentlemen who seek to enrich themselves by marrying a woman in possession of a fortune. Are there no adventurers of that kind in America?”

His tone made it clear that he was not a fortune-hunter. Merry had grown tired of gentlemen subtly informing her that they were willing to overlook her “unfortunate” nationality.

“Certainly there are,” she said. “But at home they aren’t so condescending. Here they act as if they’re doing one a favor, whereas to my mind the truth is quite the reverse.”

“You make a good point,” he conceded.

“Though I’m not being entirely fair. English gentlemen have titles for sale, and even my cousins—who are Cabots and quite powerful in their own right—don’t have anything attached to their name that directs people to bow and scrape before them.”

“I gather you are not inclined to bow and scrape before a titled gentleman?”

He didn’t seem in the least critical, which was a relief. “I am not. I prefer to judge a man on his accomplishments and character. If you have a title yourself, sir, I apologize for being so direct.”

He smiled, which she took to mean that he was untitled. “Have you met many peers…any dukes, for example?”

“I have met the Duke of Villiers, and just a few minutes ago, the Prince of Wales.” Merry lowered her voice to a whisper. “To be frank, each seemed to feel that his titles made him as special as a five-legged calf. Though to be fair, the duke might inspire reverence on the basis of his coat alone.”

His bark of laughter appeared to surprise him as much as it did her.

“Now if you will excuse me, sir, I must return to the ballroom.” Merry was fairly certain that Cedric had no concerns about her faithfulness, but there was no reason to cause a scandal by being caught in a tête-à-tête.

He didn’t move. “Tell me, do you consider yourself representative of American ladies?”

“In some respects,” she said, hesitating.

His smile deepened. “How do American ladies compare to their English counterparts?”

“Well, American ladies prefer to speak rather than warble,” Merry said, with a mischievous grin. “We never faint, and our constitutions are far hardier than those of delicate English gentlewomen. Oh, and we add tea to our milk, rather than the other way around.”

“You are of the impression that ‘delicate’ characterizes the fair sex as represented tonight in Lady Portmeadow’s ballroom?”

Merry pursed her lips, thinking of the hawk-eyed ladies who ruled over London society. “Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that Englishwomen aspire to delicacy, and American women do not. For my part, I believe that a woman’s temperament is something she ought to be able to decide for herself. I have no plan to have an attack of the vapors now, nor shall I in the future.”

“I’ve heard about these ‘vapors,’ but I have yet to see a woman faint,” he said, folding his arms over his chest.

He had a nice chest. Her eyes drifted all the way down to his powerful thighs, before she recovered herself and snapped her gaze back to his face. His expression was unchanged, so hopefully he hadn’t noticed her impropriety.

Still, in the back of her mind, she admitted that Aunt Bess was right: on the right man, snug silk pantaloons were an undeniably appealing fashion.

He was patiently waiting for her to respond. He had a kind of power about him that had nothing to do with fashion. Now that she thought of it, she had seen that kind of self-possession before: in the Mohawk warrior she’d met as a girl.

She shook her head, pushing the thought away. “Not even once? In that case, you’re either lucky or remarkably unobservant. Didn’t you notice the fuss earlier this evening when Miss Cernay collapsed?”

“I arrived only a quarter of an hour ago. Why did Miss Cernay faint?”

“She claimed a mouse ran up her leg.”

“That is highly improbable,” he remarked, a sardonic light in his eyes. “Lady Portmeadow is notorious for her frugality, and not even mice care to starve.”

“Miss Cernay’s claim is not the point,” Merry explained. “She was likely groped by Lord Ma—by someone, and fainted from pure shock. Or perhaps she feigned a swoon to avoid further indignities. Either way, I promise you that an American lady would have taken direct action.”

He unfolded his arms and his eyes narrowed. “Am I to infer that you know who this blackguard was because he groped you as well?”

“‘Grope’ is perhaps too strong,” Merry said, noticing the air of menace that suddenly hung about those large shoulders. “‘Fondle’ would be more accurate.”

Her clarification didn’t improve matters. “Who was it?” he demanded. His brows were a dark line.

She certainly didn’t want to be responsible for an unpleasant confrontation. “I haven’t any idea,” she said, fibbing madly.

“I collect that you did not faint.”

“Certainly not. I defended myself.”

“I see,” he said, looking interested. “How did you do that, exactly?”

“I stuck him with my hatpin,” Merry explained.

“Your hatpin?”

She nodded, and showed him one of the two diamond hatpins adorning the top of her gloves. “In America, we pleat silk gloves at the top and thread a hatpin through. They hold up your gloves, but they can also be used to ward off wandering hands.”

“Very resourceful,” he said with a nod.

“Yes, well, the lord in question might have squealed loudly,” she told him impishly. “Everyone might have turned around to look. And I might have patted his arm and said that I knew that boils could be very troublesome. Did you know, by the way, that a treatment of yarrow is used for boils, but it will also stop a man’s hair from falling out?”

She could feel herself turning pink. He had no need of that remedy. Although cropped short, his hair was quite thick, as best she could see on the shadowy balcony.

But he gave a deep chuckle, and Merry relaxed, realizing that it was the first time all week—perhaps even all month—she felt free to be herself. This man actually seemed to like it when a bit of information escaped from her mouth.

“Happily, I am ignorant about boils,” he said. “Are American ladies typically knowledgeable about such matters?”

“I can’t help recalling facts,” she confessed. “It’s a sad trial to me because it’s hard to remember in time that they ought not to be shared.”

“Why not?”

The corners of the man’s stern mouth had tipped upward in a most beguiling fashion. In fact, she found herself starting to lean toward him before she caught herself.

“There are few acceptable topics of conversation in London. It is quite wearying to try to remember what one is allowed to discuss,” she said with some feeling.

“Bonnets, but not boils?”

He must be something of a rake, Merry decided. The way his eyes laughed was very alluring.

“Exactly,” she said, nodding. “British ladies are discriminating conversationalists.”

“Don’t tell me you have ambitions to master the art of saying nothing.”

Merry laughed. “I fear I shall never become an expert at fashionable bibble-babble. What I truly dislike,” she said, finding herself confiding in him for no reason other than the fact that he seemed genuinely interested, “is that —”

She stopped, realizing that the subject was leading her to insult his countrymen. She was still a guest in this country, at least until she married Cedric; she should keep unfavorable opinions to herself.

The expression in his eyes was intoxicating, if only because no one else she’d met was interested in the impressions that an American had of their country. She loved London, if the truth be told: it had marvelous public gardens, for one thing.

But there were aspects of polite society that she found tiresome. “It’s the way people speak to each other,” she explained, choosing her words carefully. “They are clever, but their cleverness so frequently seems to take the form of an insult.”

Merry felt her cheeks growing warm. He must think her a complete simpleton. “It’s not that I don’t appreciate a witticism. But so very many remarks come at someone’s expense.”

He frowned at that. “Such people talk nothing but nonsense, and you should ignore them,” he ordered.

“Indeed, I am learning both to modify my subjects of conversation and to control my temper.”

“Admirable goals. Though I believe I’d like to see you in a passion.”

“You may mock me if you like, sir, but I can tell you that it is perishingly difficult for an American to transform herself into the perfect English lady! You should try it.”

He had a very appealing dent in his cheek when he smiled. “I’m quite sure I would fail. For one thing, I wouldn’t look anywhere near as appealing in a gown as you do. Englishwomen are delicate, and I am not.”

He was right about that. He was uncommonly large.

“Do you, in fact, know why Americans add tea to their milk rather than the other way around?” he asked, returning to her earlier claim.

“Because it is the correct way to do it, of course,” she said, twinkling at him.

He shook his head. “Here’s a fact for you. Your countrymen add boiling tea to their milk in order to scald it, in case its quality is not all one would wish.”

“Oh for goodness’ sake,” she cried. “Don’t tell me you’re as ignorant of Americans as everyone else at this ball! My aunt’s housekeeper would die of humiliation before she would serve milk that wasn’t absolutely fresh.”

“Then why do Americans put milk in their cup first?”

“It tastes better. The only reason English people do the reverse is to demonstrate that their china is of the very best quality and won’t break. Inferior china cracks immediately if you pour in scalding water without first cooling it with milk. And before you ask, we Bostonians drink from the very best Chinese porcelain.”

Rats. She’d been waving her hands about, which was one of the habits she was determined to curb. Cedric had mentioned more than once that ladies should not resemble Italian opera singers.

The way this gentleman could smile with only his eyes was quite…

She really should return to the ballroom before she did something foolish. “If you will excuse me, sir, I really must allow my dance partner to find me.” She gave him a smile. “Or rather, fetch me. I’ll bid you good night.”

When he still didn’t move, she began to edge around him.

“Do satisfy my curiosity,” he said softly. “Why on earth did American gentlemen leave you free to voyage to England and enjoy our season?”

He had no business looking at a betrothed woman with that gleam in his eye, though of course, he was unaware she was engaged, since her diamond was concealed by her glove. He took a step toward her, close enough that she could feel the heat of his body.

And then his eyes moved to her mouth, for all the world as if he were as consumed by desire as Bertie used to be.

That was a nonsensical comparison, because he was an English gentleman and even a fool could tell that this man had complete control over himself and his emotions.

His eyes moved lower still, to her gloved hands. He frowned. “Are you married?”

“No!” she said hurriedly. “The truth is… The truth—” She should tell him that she had become betrothed to Cedric that very evening. But for some reason she blurted out a different truth.

“I earned myself a reputation.”

He stared at her for a second. “You surprise me.”

“Not that sort of reputation! It’s just that I—well—to be honest, I have fallen in love more than once. But I wasn’t truly in love, because each time, I came to see that it had all been a terrible mistake. I had to break off two betrothals.”

He shrugged. “You’ve learned a valuable lesson about that overrated emotion, love. Why should that earn you a reputation?”

“I’m appallingly inconsistent,” she explained. “I truly am. I made a particularly regrettable choice with my second fiancé, who was far more interested in my fortune than my person. He sued me for breach of promise, and everyone learned of it.”

“Surely that speaks ill of him, not you,” he said, clearly amused.

“There was nothing funny about it,” she said tartly. “Dermot had borrowed on his expectations. That is, the expectation that he would marry me.”

“Did the suit go to trial? I can’t imagine that a jury would award damages to such a b—” He stopped. “Such a blackguard.”

“Oh, it didn’t go that far. My uncle settled the case. But I’m afraid that the news spread, and because I’d broken off my previous betrothal, there are those who said that I am…”

“Chronically faithless?”

And, at her nod, “What happened to your first fiancé?”

“Bertie had a lovely nose, but he was terribly bellicose,” she confessed.

“I have never thought much about noses,” the gentleman observed. He bent slightly to look at her nose, almost touching her.

Merry’s mouth went dry. He smelled wonderful, like starched linen and wintergreen soap. She licked her bottom lip and for a second his eyes caught there before he rocked upright. He looked completely unmoved, whereas Merry’s heart had started pounding in her chest.

“Your nose is quite lovely,” he said.

“As is yours,” she blurted out. It was. Merry was something of a connoisseur, and his nose wasn’t too sharp or too narrow or too wide. It was just right.

“I could be bellicose,” he suggested.

Merry felt a sense of breathless pleasure that almost made her giggle. “Have you engaged in any duels?” she asked, putting on a severe expression.

“Not one.”

“Bertie had two.”

“That seems—”

“During the single month we were betrothed,” she clarified.

“Perhaps he was provoked?” There was something thrilling in his eyes. “I can imagine that a man betrothed to you would not take kindly to other gentlemen’s attentions.” His eyes stayed, quite properly, on her face, and yet her entire body prickled with heat. “I expect you garner quite a lot of attention,” he said softly. “I wouldn’t blame Bertie for wanting to keep you all for himself.”

Merry’s pulse was beating so quickly that she could hear it in her ears, like a river rushing downhill. “Actually, both opponents had accidentally jostled him in the street,” she managed. “The duels had nothing to do with me.”

“Bellicose, indeed,” he murmured.

His voice enveloped her like a warm cloak, and Merry had the sudden dizzying idea that the balcony had broken away from the rest of the house, leaving the two of them stranded on a dark, warm sea.

“When I returned his posy ring, I thought I might be challenged,” she said, trying to lighten the atmosphere.

“He gave you a posy ring? In England those are exchanged between young girls. An apprentice might give one to his sweetheart.”

“It was quite pretty,” she said, defending Bertie. “The flowers spelled out my name.”

“Really,” he drawled. Somehow, she didn’t know quite how, he had eased even closer to her. She could feel his breath on her cheek. “How in the hell does a posy spell anyone’s name?”

“With the language of flowers,” she said, starting to babble. “Each flower means something, so you communicate as if you were speaking French.” Her voice faltered because his dark eyes were so intent. “Or something,” she whispered, her voice just a thread.

A sudden burst of music sounded from the ballroom and Merry jumped. “I should—”

“But first you must tell me the rest of the story.”

Something about his voice commanded obedience, and even though Merry never allowed herself to be ordered about, she found herself answering. “It’s not merely a story,” she said, giving him a little frown. “I was heartbroken to return Bertie’s ring. And Dermot’s as well.”

She suspected that he saw through her last claim of heartbreak. “So you returned Dermot’s posy as well.”

Merry found a smile trembling on her lips. “He didn’t give me a posy. He was very proud of his golden hair, and so he had a ring made from it.”

A moment of dead silence followed, and then the gentleman threw back his head and roared with laughter.

Merry found that she was grinning as well. Dermot’s lawsuit had been so unpleasant that she tried never to think of him, but laughter made the pinch of humiliation easier to take.

“So you came to London as a result,” he said, finally, his eyes still glinting with laughter.

“My aunt feared that no one would ask for my hand.” She shouldn’t be on this balcony, in the dark, talking to a man like this. She should tell him that a gentleman had, indeed, asked for her hand and she had accepted.

“Your aunt undervalues your charms. I am certain that most men in America would simply assume that you had yet to meet the right man. And that when you did, you would settle as happily as a bird in its nest.”

His eyes were on her unfashionably full lips, and then they drifted down to her equally unfashionable bosom, covered by little more than a few twists of rosy silk.

She took a deep breath, which didn’t help things because she caught a whiff of starched linen again and, beneath that, something more elusive, more compelling. Male. Color was rising in her cheeks, so she fixed her eyes on his jaw.

“In my opinion, you would be considered an excellent prospect whether you had discarded three or thirty fiancés,” he said.

When she ventured to glance back at his face, she saw that he was addressing her forehead in a most proper fashion. All the same, the roughness in his voice sent a wanton thrill down Merry’s legs. She suddenly imagined him rumpled and sweaty, his chest heaving.

Her own foolishness was like a shower of cold water. What on earth was she doing? “Thank you,” she said, nodding madly. “That is kind of you, and it has been a pleasure to converse.” Without further ado, she stepped around him and turned toward the ballroom.

A large hand curled around her waist, neatly spinning her about and bringing her up against him.

Sensations skittered through her at the press of a hard male chest against hers. Miss Fairfax would have been appalled. Yet rather than pull away, Merry froze, looking up at him with her heart pounding in her ears.

“Who groped you?” he demanded.

“Who had made you so angry before you came onto the balcony?” she countered. What—or who—on earth would make a man like this so enraged?

“My fool of a brother. And now I’d like to you to answer my question.”

She had already forgotten what he had asked. His gaze was so intense that she felt confused and flushed. She would never allow a man—a complete stranger—to kiss her, if that’s what he was contemplating.

“What was your question?” she asked, wincing inwardly when her voice came out as breathless as a siren’s.

“Who groped you?” he repeated.

He had that warrior look in his eyes that Merry found absurdly compelling. She came out with the truth before she could think better of it. “Lord Malmsbury…Lord Malmsbury lets his hands stray where they shouldn’t.”

“Stay away from him,” he ordered, scowling.

“I appreciate your concern,” Merry said with dignity as she pulled free and stepped back, “but there’s no call to order me about. I have already decided to avoid his lordship—not that he has shown the slightest inclination to deepen our acquaintance, thanks to my hatpin.”

“Between your weapon and his boils, I doubt he will risk further encounters.” His smile reappeared. “I trust that after we are formally introduced, I may request a dance, if I promise not to grope you.” His hand fell from her waist.

It occurred to Merry that she would rather like to be groped by this man. It was a appalling realization. She was betrothed.

He executed a perfect bow.

She dropped a curtsy, and this time did her governess’s instruction proud, nearly grazing the ground with her knee.

Merry walked back into the ballroom without looking back; no matter what Miss Fairfax thought, she possessed self-control. Plenty of it.

She had almost reached the other side of the room before she turned her head and looked back.

He was nowhere in sight.

She took a seat along the wall and gave herself a good talking-to. What on earth was she thinking? Was she truly as fickle as the gossips back home believed? She may have made mistakes choosing her first two fiancés, but she had never been truly capricious.

She had truly believed that she was in love with both Bertie and Dermot. She had never flirted with a man while betrothed to another.

Not that she had precisely flirted with this man.

All right, she had flirted.

Merry groaned silently. Why hadn’t she slapped him when he caught around her waist, or at the least announced her status as a soon-to-be married woman? Instead, she had just looked up at him like a silly widgeon waiting to be kissed.

No wonder he’d been so amused. He likely thought her the veriest green girl, knocked head over heels by the magnificence of his black-clad presence.

It was all so embarrassing.

The next time she encountered him, she would have to emphasize that she was in love, and had scarcely given their conversation a second thought. Perhaps she would say something like, “Oh, we’ve met, have we not? I declare, I forgot all about it!”

“There you are, m’dear,” her aunt said, appearing before her. “Cedric came by with a glass of wine for you.” Bess thrust a brimming glass into Merry’s hand. “The boy is endlessly considerate, I must say.”

“Thank you,” Merry said.

“He returned to the card room with your uncle,” Bess said. “You’ll see him later; we’ll be taking your beau home in our carriage, because his vehicle threw an axle or something of that sort. You should have seen how graciously he accepted your uncle’s offer. His manners are just miraculous! Why, he’s as polished as wax.”

“‘As polished as wax,’” Merry repeated, pulling herself back together. That conversation on the balcony meant nothing. She’d probably never meet the man again. “Aunt Bess, that doesn’t make any sense. You use wax to polish things.”

“You know what I mean,” Bess said, unperturbed. “The boy shines like brass.”

Merry frowned.

“Oh, tut!” her aunt said. “You’re lucky to have him, my dear, and that’s all I’ll say about it.”

As Merry began to explain (not for the first time) the concept of mixed metaphors, one of her suitors, a Mr. Kestril, approached, and after greeting them both, said, “Miss Pelford, I believe you granted me your next dance.”

“Certainly,” Merry said, smiling at him. Cedric had suggested that Merry keep Mr. Kestril at a distance because he wasn’t “good ton,” whatever that meant.

But Merry liked him; Mr. Kestril knew quite a lot about gardening, so he was never boring.

“As shiny as an ingot from a fairy hill,” her aunt said abruptly.

Mr. Kestril’s forehead creased. “I beg your pardon?”

“I had described Merry’s fiancé, Lord Cedric, as being as shiny as brass, but I’m trying to come up with something better,” Bess explained, dropping the fact Merry was engaged neatly into the conversation. “My Muse just suggested a comparison to a fairy ingot.”

“My aunt is a poet,” Merry told Mr. Kestril, whose mouth had pulled tight at the mention of her betrothal.

“Nothing so grand,” Bess said, fanning herself. “A poet implies subtlety and genius. I merely dally with words.”

“There’s a touch of genius in your comparison of a fairy ingot to Lord Cedric,” Mr. Kestril said dryly.

Merry frowned. “Why so? A fairy ingot is gold, isn’t it?”

“And Lord Cedric’s hair is golden-colored,” Bess explained.

The strains of a country dance started up. “Miss Pelford,” Mr. Kestril said, bowing deeply and extending his hand. “If I may?”

She put her hand in his. And with that, they were away, capering down the room, and smiling every time they met and parted, and met and parted again.

Merry kept her eyes on her partner’s face and glanced neither right nor left. Not that there was anyone she’d want to see in the ballroom.

Other than her fiancé, of course.

end of excerpt

My American Duchess

by Eloisa James

is available in the following formats:

UK Print:

UK Digital:

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.